Are you someone who purchases plants and hopes for the best? Or do you like to know every detail, like how much sun, what soil type or how big they grow? We should always bear in mind “the right plant for the right place”. One such consideration is a plant’s hardiness. The UK and US hardiness zones exist to point both professional and private gardeners in the right direction when making informed decisions. After all, no one wants to plant out something stunning which will have vanished by the following spring!

A brief background

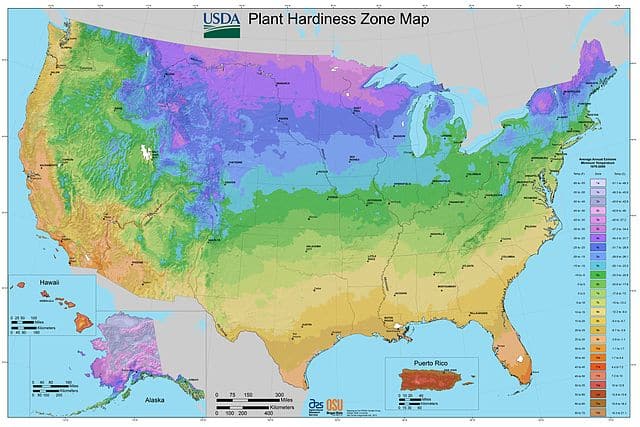

The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) produces the American hardiness zones map, and it was they who created the definitive version back in 1960. The initial idea came about in the 1920s and 30s however.

It’s no surprise the US formulated the concept. They have a much larger land mass to oversee, composed of a wide range of temperatures. Zoning the continent creates a much quicker reference guide than having to look up each city individually. Director of the US National Arboretum Henry Skinner originally split his country into ten zones based on gradients of 10°F. In 1990, the USDA added Mexico and Canada. Additionally, officials split each zone in half, giving 5°F differences (labelled a and b). Two further zones have since been added (2012), giving 13 zones in total now. It’s interesting to note how lower temperatures have shifted northwards. Does this evidence global warming or greater scientific accuracy?

A rival US zone map did exist, from the Arnold Arboretum, and this was in fact the older of the two. It fell out of use by 1990, leaving the USDA version as the basis of subsequent international maps, including our own UK copy. The Royal Horticultural Society devised its own Hardiness Ratings in 2012.

The RHS Hardiness Ratings

From a broader viewpoint, the UK only corresponds to American zones 7 to 10. Thanks to the North Atlantic Current, we have a temperate maritime climate – much milder than other countries on similar latitudes. This gives us more leeway in the plants we choose, but don’t be fooled. In elevated and exposed positions like the Pennines and Scottish Highlands, temperatures can still plummet to -20°C. Conversely, the Scilly Isles may experience lows of only 1°C in midwinter.

The RHS’s classification offers the British gardener a more in-depth perspective on plant hardiness. It separates the four US zones into nine ranks. H1a represents the most tender of specimens, the tropical exotics. This is followed by H1b and H1c, then 2 etc. H7 comes last and identifies plants fully hardy for the Brits.

Anything in the H1a zone will need constant protection indoors as it will only survive temperatures above 15°C.

What about our American readers?

If you could own properties at opposite ends of the North American continent, you could indulge in whichever plants took your fancy! More realistically, you’ll still find yourself limited by your local climate. Living in Alaska, you’ll have to deal with lows of -60°F (-51.1°C) which is zone 1a. There’s not much that can thrive in such harsh conditions.

Conversely, on the Hawaiian coasts you’ll experience temperatures bottoming out at 60°F (15.6°C), equating to zone 13a. This offers you great potential when it comes to lush tropical foliage, although your more temperate desires might be tempered.

However…

However…

Hardiness is all well and good, but it fails to take into account a plant’s drought tolerance – the opposite extreme. When it comes to this, as with all other factors, consider where the plant originates from. An alpine species will cope much better with extremes of temperature and light, while a native bog plant won’t enjoy too free draining a soil. Furthermore, the hardiness zones are no replacement to knowing your area well, as microclimates don’t enter the equation either.

Remember that hardiness zones are a guide to be employed, not a total substitute for understanding (much like closing your eyes while driving, just because the SatNav is talking at you).

Further information

Kevin Gelder

Kevin joined Bestall & Co in late 2017 and brought a range of skills with him from a varied background. He gained a degree in French and Italian from Lancaster University in 2009 before successfully completing a PGCE at the University of Sheffield in 2011. He built on his communication skills through secondary language teaching, before working in healthcare administration.

Ultimately though it was his passion for plants and gardening which brought him to Bestall & Co as a member of the planting team, and although he's now moved back to an office based role, the articles he wrote whilst he was still with us live on.

However…

However…